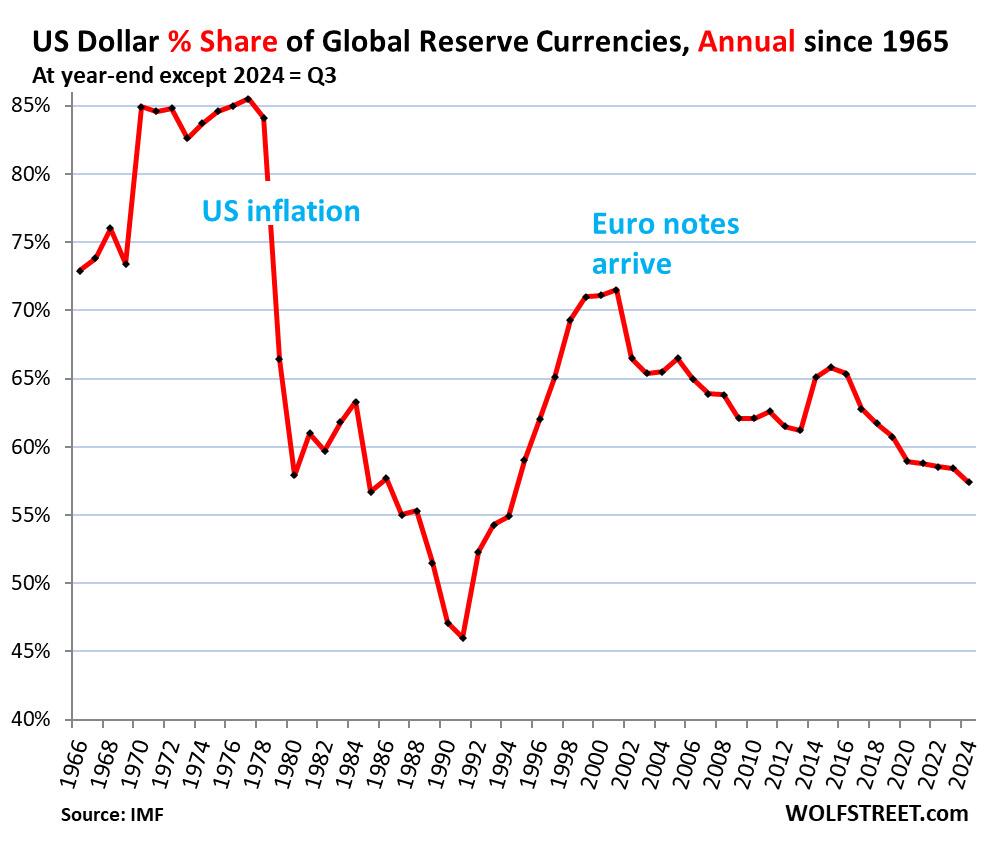

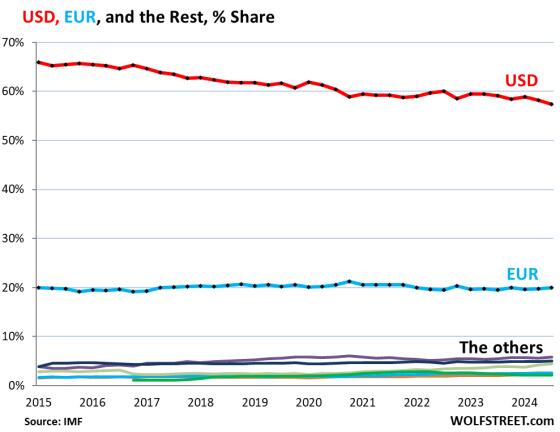

The US dollar lost further ground as global reserve currency among many reserve currencies held by central banks. Its share has been zigzagging lower for many years as central banks have been diversifying their holdings to assets denominated in currencies other than the dollar. And they’ve also been diversifying into gold. But the dollar remains by far the dominant global reserve currency.

The share of USD-denominated foreign exchange reserves fell to 57.4% of total exchange reserves the lowest since 1994, according to the IMF’s COFER data for Q3 2024. USD-denominated foreign exchange reserves include US Treasury securities, US agency securities, US MBS, US corporate bonds, US stocks, and other USD-denominated assets held by central banks other than the Fed.

In Q1 2015, the USD’s share was still 66%. Over these 10 years, the dollar’s share of global reserve currencies has dropped by 8.6 percentage points. If this pace of decline continues, the dollar’s share will fall below 50% in less than 10 years, by the end of 2034.

The dollar’s share had already been below 50% in 1990 and 1991, at the final leg of its long plunge from a share of 85% in 1977 to 46% in 1991, after inflation had exploded in the US in the 1970s, and eventually the world lost confidence in the Fed’s ability or willingness to get this inflation under control.

But by the 1990s, central banks loaded up on dollar-assets again, until the euro came along. This chart shows the dollar’s share at the end of each year (2024 = Q3).

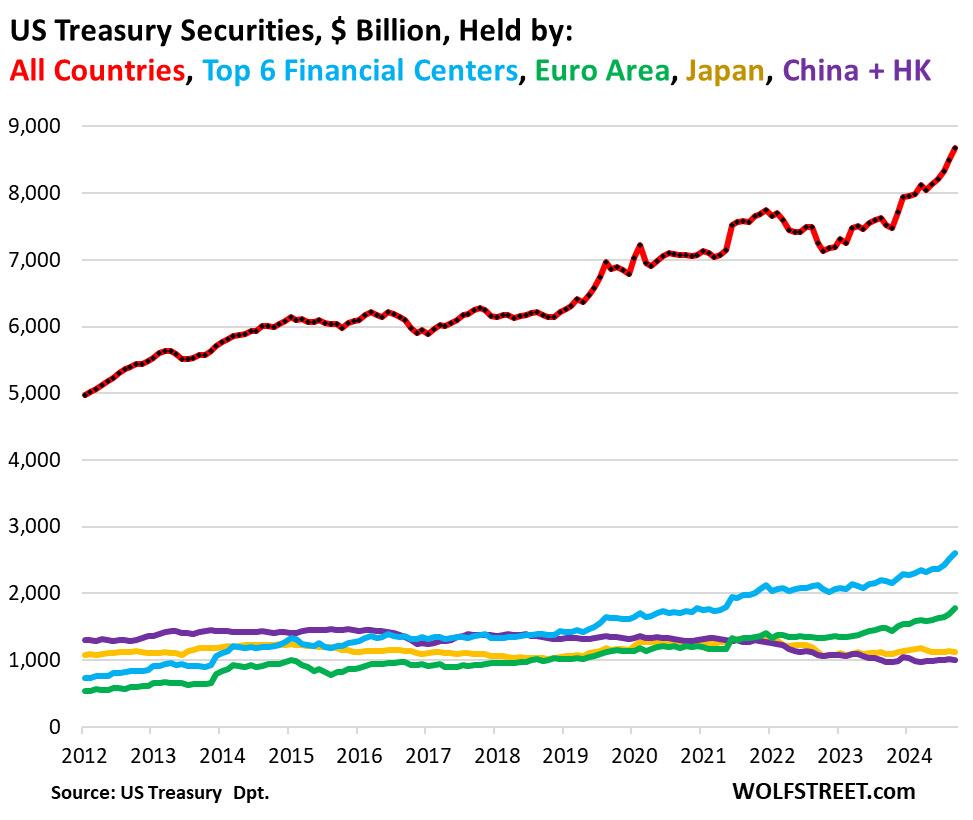

But they’re not dumping US Treasury securities.

Holdings of US Treasury securities by foreign central banks and other foreign holders have surged from record to record. Over the past 12 months, foreign holders added $880 billion, bringing their stash to a record $8.67 trillion, according to the Treasury Department’s TIC data earlier (we discussed the details here).

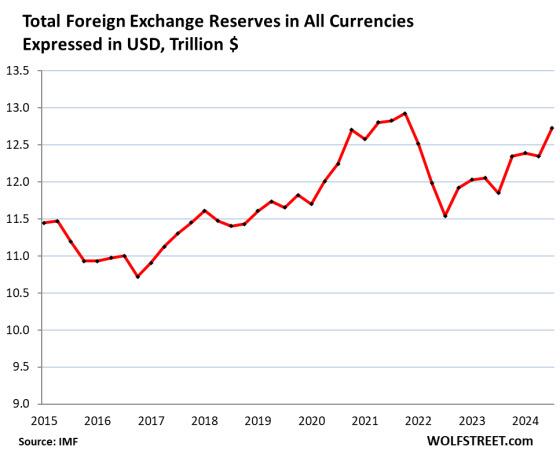

Total foreign exchange reserves.

Central banks holdings of foreign exchange reserves denominated in all currencies, including in USD, rose to $12.7 trillion.

Excluded from the total are any central bank’s holdings of assets denominated in its own currency, such as the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities and MBS, the ECB’s holdings of euro-denominated bonds, and the Bank of Japan’s holdings of yen-denominated assets.

Top holdings, expressed in USD:

- USD-denominated assets: $6.77 trillion

- EUR-denominated assets: $2.37 trillion

- YEN-denominated assets: $0.69 trillion

- GBP-denominated assets: $0.59 trillion

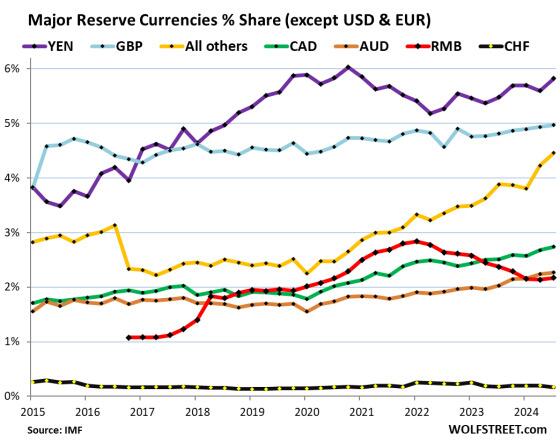

The other major reserve currencies.

The euro’s share, #2, ticked up to 20.0%, the highest since 2022. But the movements have been small. The euro’s share has been around 20% for years (blue in the chart below).

The other currencies are the colorful tangle at the bottom of the chart. More on those in a moment.

The rise of the “nontraditional reserve currencies.”

We will now hold a magnifying glass over the colorful tangle at the bottom of the chart above.

These other currencies, except for the Chinese renminbi, have all been gaining share, at the expense of the dollar, while the euro’s share has remained roughly stable.

This includes the basket of “nontraditional reserve currencies,” as the IMF calls them, that are combined into “All others” (yellow in the chart below), whose combined share has been surging since 2020.

China is the second largest economy in the world, but its currency plays only a small role as a reserve currency. And it has lost ground against the USD and other currencies since 2022.

In 2016, the IMF had added the RMB to its basket of currencies backing the Special Drawing Rights (SDR). That was a big step, and lots of folks thought that the RMB would quickly become a threat to the dominance of the USD as global reserve currency.

But central banks have not been enamored with RMB-denominated assets for a variety of reasons, including capital controls, convertibility issues, and other issues. Last year, the RMB was surpassed by the Australian dollar (AUD).

Far behind the USD and the EUR, the largest currencies by share:

- Japanese yen, 5.8% (YEN, purple).

- British pound, 5.0% (GBP, blue).

- “All other currencies” combined, 4.5% (yellow).

- Canadian dollar, 2.7% (green).

- Australian dollar, 2.3% (brown).

- Chinese renminbi, 2.2% (red).

- Swiss franc, 0.2% (blue).

Central banks diversify from the USD to other currencies.

The IMF found that there were 46 “active diversifiers” among central banks, including central banks in most of the G20 economies, according to a paper it published in 2022. It defined them as central banks that had at least 5% of their foreign exchange reserves in “nontraditional reserve currencies.”

Two factors contributed to the rise of the “nontraditional reserve currencies,” the IMF found:

- The growing liquidity of assets denominated in “nontraditional reserve currencies,” which makes them easier for central banks to trade in the quantities they deal with.

- Chasing higher-yielding assets elsewhere during the 0%-era in the US and Europe.

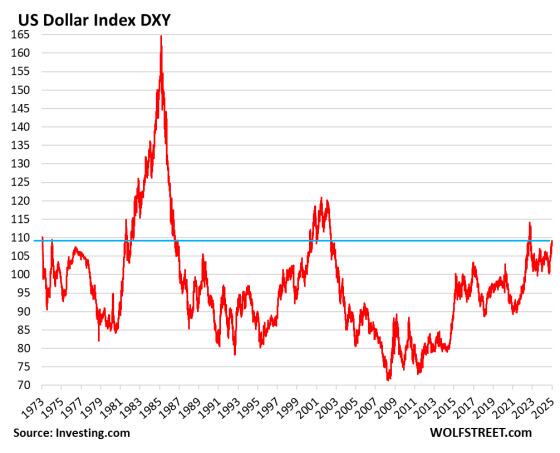

USD exchange rates impact foreign exchange reserves.

The USD has risen sharply against a basket of other currencies in recent months, as tracked by the Dollar Index [DXY], but remains below the 2022 high, well below the 2001 high, and hugely below the 1985 high. So we see these huge peaks and valleys, but now the dollar is about where it had been in 1977.

The DXY is dominated by the euro and the yen, the two largest trade currencies behind the USD. When euro arrived on the scene, the DXY’s local currencies that became part of the euro were replaced by the euro. At the DXY was started in 1973. Today it’s at 108.9 about where it had been during the high moments in 1973-1975 (data via YCharts):

Why this matters: The IMF reports foreign exchange reserves in USD. USD holdings are obviously reported in USD. But the holdings in EUR, YEN, GBP, CAD, RMB, etc. are translated into USD at the exchange rate at the time. So the exchange rates between the USD and other reserve currencies impact the magnitude of the non-USD assets – but not of the USD-assets.

For example, the Bank of Japan’s holdings of USD-denominated assets, expressed in USD, don’t change with the YEN-USD exchange rate. But its holdings of EUR-denominated assets are translated into USD at the EUR-USD exchange rate at the time. So the magnitude of Japan’s holdings of EUR-assets, expressed in USD, fluctuates with the EUR-USD exchange rate.

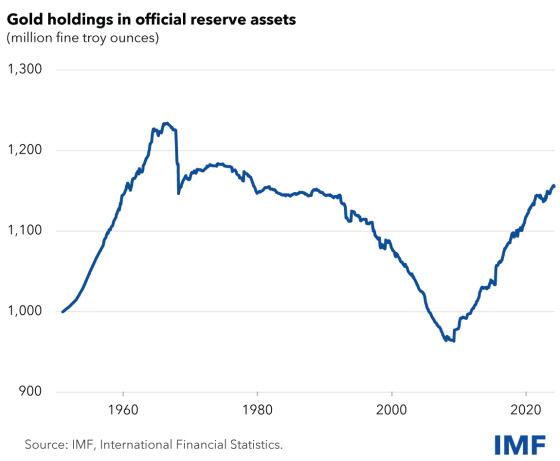

The other diversification: gold.

Gold bullion is not a “foreign exchange reserve” asset of central banks, and is not included in the data above. Instead, it’s a “reserve asset,” not involving foreign currency.

Central banks had spent decades unloading their gold holdings. But about 10 years ago, they started rebuilding their stash.

According to the IMF, central banks’ gold holdings have surged over this decade to 1.16 billion troy ounces – roughly $3.08 trillion, compared to $12.3 trillion in foreign exchange reserves (chart via the IMF)

By Wolf Richter of WolfStreet.com via Zerohedge.com